Joe Collum is the author of three books. His novel Brady’s Run, a murder mystery set in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, was published in 2009. Et Tu Brady, the sequel to Brady’s Run, was published in 2013. His next novel, A Bullet for Brady, will be published in 2016. The Black Dragon: Racial Profiling Exposed, the true story of the invention and fight to end the practice of racial profiling, was published in 2010.

Prior to becoming an author, Collum was an investigative reporter whose stories led to a Congressional investigation on elder care, saved thousands of poor people from losing their homes, revealed the deaths of jail inmates due to lack of medical care and led to the incarceration of more than 40 individuals for public corruption.

He was the first reporter in America to expose the practice of racial profiling (the Oxford English Dictionary credits him with coining the term). His final assignment was at Ground Zero on September 11, 2001, and the days immediately following the collapse of the World Trade Towers. His account of the tragedy is excerpted in the book “Covering Catastrophe.”

During his 27-year career, Collum was the recipient of more than 100 major journalism awards, including the DuPont-Columbia Silver Baton, two George Polk Awards, five Investigative Reporters & Editors Awards, two Sigma Delta Chi Bronze Medallions, the Ohio State Award, the National Headliner Award, the American Bar Association Silver Gavel and a dozen Emmy Awards.

We caught up with him to learn more about his time at The Alligator and his storied career.

When did you work at The Alligator? What led you there?

After I realized as a kid that I’d never realize my dream of playing shortstop for the New York Yankees, I decided I wanted to be a writer. When I got into UF, I enrolled in a journalism class, which I thought might be an avenue to get into writing. (Journalism 101 was the only journalism course I ever took.) The J-School in those days was located in the bowels of the football stadium. I remember earning a grade of “C” in the class and my professor advising me NOT to pursue a career in journalism!

The best thing that happened in that class, however, was meeting a student who worked at The Alligator who recommended I apply for a job. That was 1972. I spent the next two years at the newspaper, eventually serving as Features Editor and, for one summer, Sports Editor (perhaps the worst in The Alligator’s history).

I loved every minute of it.

What do you do now?

I retired from journalism a month after 9/11 and moved home to Fort Lauderdale to write books (and play way too much golf).

What are some of your strongest memories from your time at The Alligator?

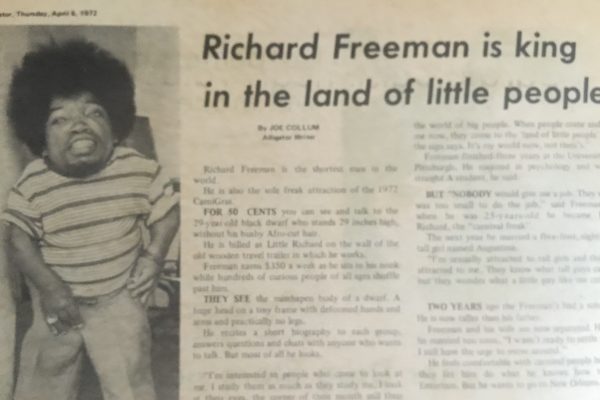

I’ll never forget the first story I wrote for The Alligator. I was assigned to cover CarniGras, the annual UF campus carnival across from Florida Field. “Just go find a story,” the news editor told me. I found a guy in the Freak Show named Little Richard, the world’s shortest man! Little Richard was a black man who stood 2-feet 9-inches tall and was married to a 5-foot 8-inch Swedish blonde. My story was published April 6, 1972 (I kept a scrapbook of my Alligator stories). From that moment on, I was hooked on journalism.

I loved the fact that I could go out, find an interesting story, and the next day tens of thousands of people could be reading my words.

Over the next two years, I wrote dozens of articles for The Alligator, including a profile of the UF professor who invented frozen orange juice, the UF professor (Dr. Robert Cade) who invented Gatorade and the former UF professor (James Dickey) who wrote Deliverance. Mainly, though, I remember the joy that came from learning to craft stories, massage language and find ways to grab readers and try to drag them into the pieces I wrote.

How did your time at The Alligator prepare you for your career?

Because I was not a journalism major, the only material I had to show to find a job were the clips I generated working at The Alligator. Fortunately, they were enough to get me hired in 1974 for my first reporting job at Today newspaper (now Florida Today) in Cocoa Beach, where I could surf every morning and work afternoons and nights. Six months later, I was offered a $12 a week raise and moved to Tampa to work at the late, great Tampa Times, a small afternoon daily.

This all happened during the time Watergate was rocking America and making heroes out of a couple of Washington Post reporters who brought down a president. Having grown up during the Vietnam War, assassinations, racial tumult and Watergate, I had a very jaundiced view of authority. I fell in love with the idea that I – a 23-year-old kid – could investigate mayors, police chiefs, even Congressmen and Senators, and call them to question about their deeds and possible misdeeds.

At The Tampa Times, I was lucky to work for editors who gave me a long leash to pursue any number of juicy stories involving public corruption and injustice. That was where I learned to be a real reporter. After a few years at The Times, I was offered a job as an investigative reporter at the local NBC television affiliate and spent the last 23 years of my career in broadcasting. However, I always recommend to young aspiring broadcast journalists that they get some print experience like I was fortunate to get at The Alligator, especially if they attend a college with a student newspaper.

What led to you to pursuing racial profiling as a book topic?

As an investigative reporter, I was fortunate to work at TV stations in Tampa, Houston and, finally, New York, that gave me the time and resources to dig deep into important stories. My last career stop was WWOR-TV. From the time I arrived, I began hearing stories about state troopers stopping and searching an inordinate number of black people on the New Jersey Turnpike, the busiest highway in America and the main thoroughfare in and out of New York City. In 1989, I spent several months investigating the situation.

…I began hearing stories about state troopers stopping and searching an inordinate number of black people on the New Jersey Turnpike, the busiest highway in America and the main thoroughfare in and out of New York City. In 1989, I spent several months investigating the situation.

The result was a series of reports we called “Without Just Cause,” which proved beyond doubt that troopers were targeting dark-skinned travelers on the turnpike, which was nicknamed “The Black Dragon.” Shortly after my stories aired, the longtime head of the state police – a man known as the “J. Edgar Hoover of New Jersey” – was fired and the practice of “racial profiling” came to an end, at least temporarily.

Gradually, however, profiling returned and, finally, exploded when troopers shot up a van carrying several innocent black students in what turned out to be a racial profiling stop. After the renowned lawyer Johnnie L. Cochran got involved, profiling became a national issue. (Cochran eventually used my 1989 stories to help win a $13 million settlement from the State of New Jersey.)

I knew that the profiling saga was an incredible story and believed I was the best person to write a book about it. But, being a father of four sons and a full-time reporter, I kept putting off the book.

Then came 9/11. I ended up standing in the rubble of Ground Zero an hour after the second tower collapsed. All I could think of was how many people had gone to work that beautiful morning only to be wiped out in the blink of an eye. I realized that tomorrow is promised to no one. If I was going to write that book I needed to do it then.

One month later, I retired from journalism and moved back to my hometown of Fort Lauderdale and began work on The Black Dragon: Racial Profiling Exposed.

One unexpected development occurred while I was writing the book when I received a call from the Oxford English Dictionary telling me they were coming out with a new edition and adding the term “racial profiling.” They said their research showed I was the first person to use the phrase in my 1989 report and they put me in the dictionary, which was pretty cool!

What piece won you and your staff at WWOR-TV the DuPont-Columbia Silver Baton Award?

The DuPont was awarded for “Flunk City,” a series of stories about a disastrous public school system. “Jersey City, the city that failed its children.” After months of investigation, we proved schools were being used as a political pork barrel to award cronies of the mayor and other office holders — few of whom sent their own children to the city’s public schools. The result was an educational system which did little to serve the needs of its minority youth. Shortly after our reports aired, the state took over the local school system, the first time such an action had ever occurred in the United States.

What have been some of the most challenging stories you’ve worked on as a reporter? What have been the most rewarding?

As a young newspaper reporter, another reporter and I had been doing stories on corruption in the Tampa police department and court system. One of our primary sources was a cop who’d been feeding us explosive inside information.

One day, someone walked up to his front door and shot him to death. The crime became perhaps the most sensational in Tampa history, and we spent more than a year working day and night uncovering details surrounding the murder. Our stories led to the appointment of a special prosecutor, and eventually several individuals were convicted of killing our source as part of an organized crime murder conspiracy.

In Houston, my I-Team partners and I broke a number of big stories. One involved the cover-up by doctors of anesthesia mishaps that killed or destroyed the lives of more than two dozen victims at local hospitals.

We also exposed an unscrupulous home repair and finance company that duped thousands of poor black and Hispanic residents, many of whom couldn’t read the contracts they were signing. A large number of them ended up losing their homes to foreclosure before we blew the cover on the operation.

We found more than a half-billion dollars in untaxed property owned by oil and gas exploration companies in Houston, the petrochemical capital of America.

Our investigation into a national nursing home chain led to a Congressional investigation of elder care.

My investigation of the Harris County jail in Houston revealed that nine inmates had died in the previous 18 months due to inadequate medical care.

In New York, our investigative unit uncovered high levels of lead in school drinking fountains. A five month investigation revealed the tragedy that was the foster care system in New York City. Another investigation of welfare fraud led to the indictment of several dozen individuals, most of whom were so-called “public servants.”

The most rewarding may have been our racial profiling investigation, if only because it is an issue that still resonates today.

What advice do you have for current reporters at The Alligator who want to pursue investigative reporting?

Get it right! I’m proud to say I never had to retract a story because of factual error. Take your time at The Alligator to dig into the stories you come across. The best stories are often the ones you stumble across while working on other stories. The resources available today are incredibly more powerful than in my day. (Google alone didn’t exist when I was a reporter!) Learn to use all the tools at your disposal. Join Investigative Reporters & Editors (IRE), the best journalism organization in America.

Also, work your ass off. That’s the only secret to success I ever learned. Outwork everyone else.

Finally, enjoy the privilege of being a journalist. Remember you are the eyes and ears of the public — and are not only in a position to expose wrongdoing by the rich and powerful but to dramatically impact for the better the lives of the poor and powerless.

I always considered my career to be something of a scam because I was being paid (sometimes handsomely) to spend my life telling interesting stories about fascinating people and situations.

I never considered it a job. It was a gift I was lucky to fall into and will always be grateful for. And it all started at The Alligator!