Debbie Cenziper is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter at The Washington Post. Over 20 years, Debbie’s stories have sent people to prison, changed laws, prompted federal investigations and produced more funding for affordable housing, mental health care and public schools. She has won many major awards in American print journalism, including the Robert F. Kennedy Award and the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting from Harvard University. She received the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for stories about affordable housing developers in Miami who were stealing from the poor; a year before that, she was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for stories about widespread breakdowns in the nation’s hurricane-tracking system. Debbie grew up in Philadelphia and graduated from the University of Florida in 1992.

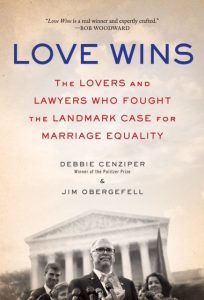

Love Wins: The Lovers and Lawyers who Fought the Landmark Case for Marriage Equality can be purchased wherever books are sold and at harpercollins.com.

What is your job now? What do you like about it, and what makes it difficult?

I have been an investigative reporter at The Washington Post since 2007. This fall, I’ll start teaching journalism at The George Washington University and working at The Post part-time. I made that transition so that I can focus on my next book.

An old newspaper editor once warned me that investigative reporting can be one of the toughest, most grueling jobs in journalism — like poking around in the dark, blindfolded, with one arm tied behind your back. But I’ve enjoyed every minute of it.

I’ve written about affordable housing developers who squandered millions of public dollars meant for the poor, slumlords who turned off the heat to force families from rent-controlled apartments, and state-run psychiatric hospitals that allowed the mentally ill — including children — to languish without care or oversight.

Over 20 years, my stories have sent people to prison, changed laws, prompted federal and Congressional investigations and produced more funding for affordable housing, mental health care and public schools.

What lessons did you learn from The Alligator that you use in your current job?

Too many to count.

I came to UF from the malls of suburban New Jersey, not particularly interested in social issues or current events. At The Alligator, I met this incredible group of dynamic, socially aware and fearless young journalists. It was a moment in time that I’ll never forget.

I learned to write on deadline. I learned to listen. I learned to care about my community.

In one of my very first stories at The Alligator, I misspelled someone’s name and was reprimanded by an editor. It made me a meticulous (ok…paranoid) fact-checker — and I am forever grateful for it.

At The Alligator, I felt free to experiment with words, ideas and story structure. Sometimes, I failed miserably. As editor, I oversaw a series about sex on campus that still makes me cringe, all these years later. I nearly busted the newspaper’s budget when I decided that staff writers were long overdue for a raise.

But when I left that newsroom, I was a journalist. I started working at the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel four days after UF graduation and won the Pulitzer Prize for local reporting at The Miami Herald 15 years after that.

How long have you been reporting on same-sex rights, and did this topic come up in your coverage at The Alligator?

As an investigative reporter, I’ve focused almost exclusively on stories about government corruption. I had never written about gay rights and had never been particularly up on the politics of same-sex marriage.

Then, in early 2015, I went to an ACLU press conference in Washington, D.C. Plaintiffs who were taking the case for same-sex marriage to the U.S. Supreme Court sat shoulder to shoulder in the front of the room. They had come together not to change the world but to protect their families, an overriding universal need that instantly moved me, both as a journalist and as a human being.

Jim Obergefell, the named plaintiff in the case, was fighting the state of Ohio for what seemed like such a simple thing: an accurate death certificate for his late husband, John Arthur.

Two years earlier, Jim and John — who was dying from ALS — had chartered a medical plane and exchanged vows on a tarmac in Maryland, where same-sex marriage was legal. But back home, Ohio refused to recognize their marriage, which meant that John would be listed as single on his death certificate when he died, with no surviving spouse.

Jim sat alongside same-sex couples whose children had been denied birth certificates that listed the names of both parents. The youngest plaintiff in the case was two years old, and he toddled around the conference room munching on strawberries as one of his fathers described the heartbreak of being forced to choose which father to list on Cooper’s birth certificate and which father to leave off, officially a legal stranger.

That afternoon, listening to a grieving widow and a group of desperate parents, the beginnings of Love Wins took shape.

When reporting the material for this book, what were the “breakthrough” moments where you knew the book was coming together?

I’m not sure I had time for a “breakthrough” moment because I had only six months to write 80,000 words. That meant reporting and writing one chapter every week from July to December in 2015. I knew right from the start that I didn’t want to write a book about history or politics. Love Wins is a story about dynamic, determined civil rights lawyers who fought in courtroom after courtroom, in four different states, until they wound up before the highest court in the land. And it’s the story of ordinary people who stepped out of their private lives to keep their families safe and secure.

I’m not sure I had time for a “breakthrough” moment because I had only six months to write 80,000 words. That meant reporting and writing one chapter every week from July to December in 2015. I knew right from the start that I didn’t want to write a book about history or politics. Love Wins is a story about dynamic, determined civil rights lawyers who fought in courtroom after courtroom, in four different states, until they wound up before the highest court in the land. And it’s the story of ordinary people who stepped out of their private lives to keep their families safe and secure.

More than anything, it is a story about the extraordinary power of love.

What made you want to pursue the same-sex marriage battle as a book subject?

The issue of same-sex marriage had always seemed rather symbolic to me until I met the plaintiffs in this case. They were facing so many tangible, technical problems, such as not being able to get birth certificates for their children that listed the names of two mothers or two fathers.

As a journalist, I’ve met hundreds of kids growing up in poverty. I once spent weeks getting to know a 10-year-old named Trenton Robinson, who was living in one of the most desolate areas of Washington, D.C. I’ll never forget him. His apartment had no heat and though his mother kept the burner of the oven on at night, Trenton could still see his breath in the darkness. There was a hole the size of a softball in the floor of his living room, and when he peered through it, he could see the basement floor, which was covered in sewage.

It was an absolute tragedy.

Yet in Ohio, there were parents with diaper bags and mini vans, living on cul-de-sacs and shopping for pediatricians and preschools. And all they wanted — all that any parent wants — was to protect their children. The very first step was getting a birth certificate that listed the names of both parents. But the state had denied that.

What were some of the most challenging moments while reporting and writing this book?

I wanted this book to appeal to a universal audience. Gay or straight, we all love, grieve and worry about our kids. I wanted to create highly relatable characters that readers would root for and celebrate.

Please share one of your most memorable experiences from your time at The Alligator.

I was editor of The Alligator in 1991. We got a tip about a UF pharmacist who was refusing to fill Infirmary prescriptions for the morning after pill because of his beliefs about abortion. That meant that female students had to quickly find a way to a pharmacy off-campus to get the pill.

My copy desk chief went in undercover and obtained a prescription from a UF Infirmary doctor. When the pharmacist refused to fill the prescription, we wrote a series of stories about it. The university removed the pharmacist.

It was my first taste of investigative reporting and I was hooked.

Other memorable experiences? Holding student government accountable and publishing a special edition when the Gators won their first official SEC football championship in 1991. We had fantastic sports editors and photographers who pulled it together, literally overnight.

Favorite place to eat on long nights (or days) at the paper?

Farah’s, which closed in 2013.

What advice would you give student staff today?

Though the media world is in a state of constant innovation, the fundamentals of journalism remain the same. Remember that accuracy gives you credibility, that fairness is more important than dramatic words and that your stories affect real people. Take that responsibility seriously — and enjoy every minute of it.

Related content: